Details

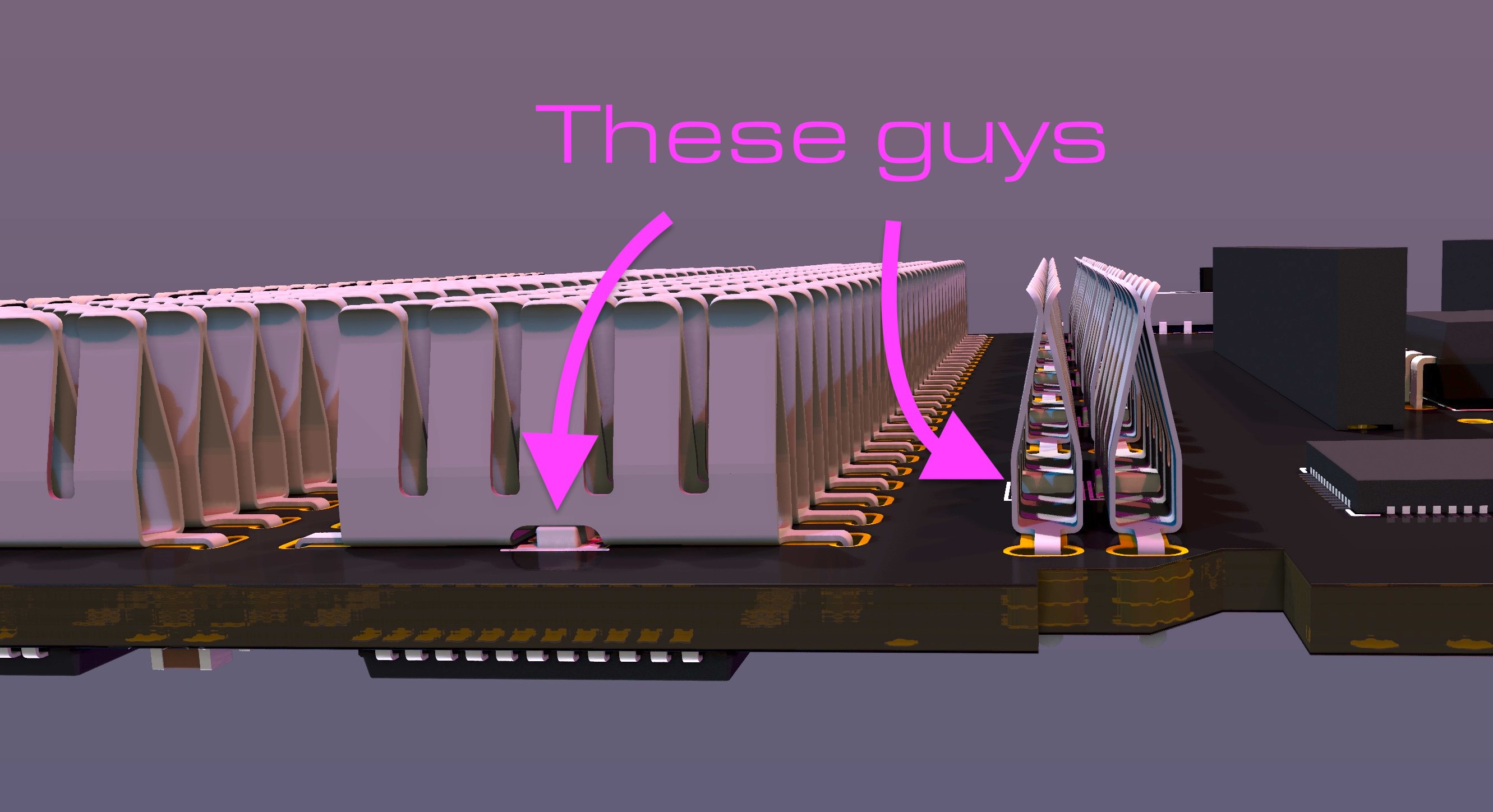

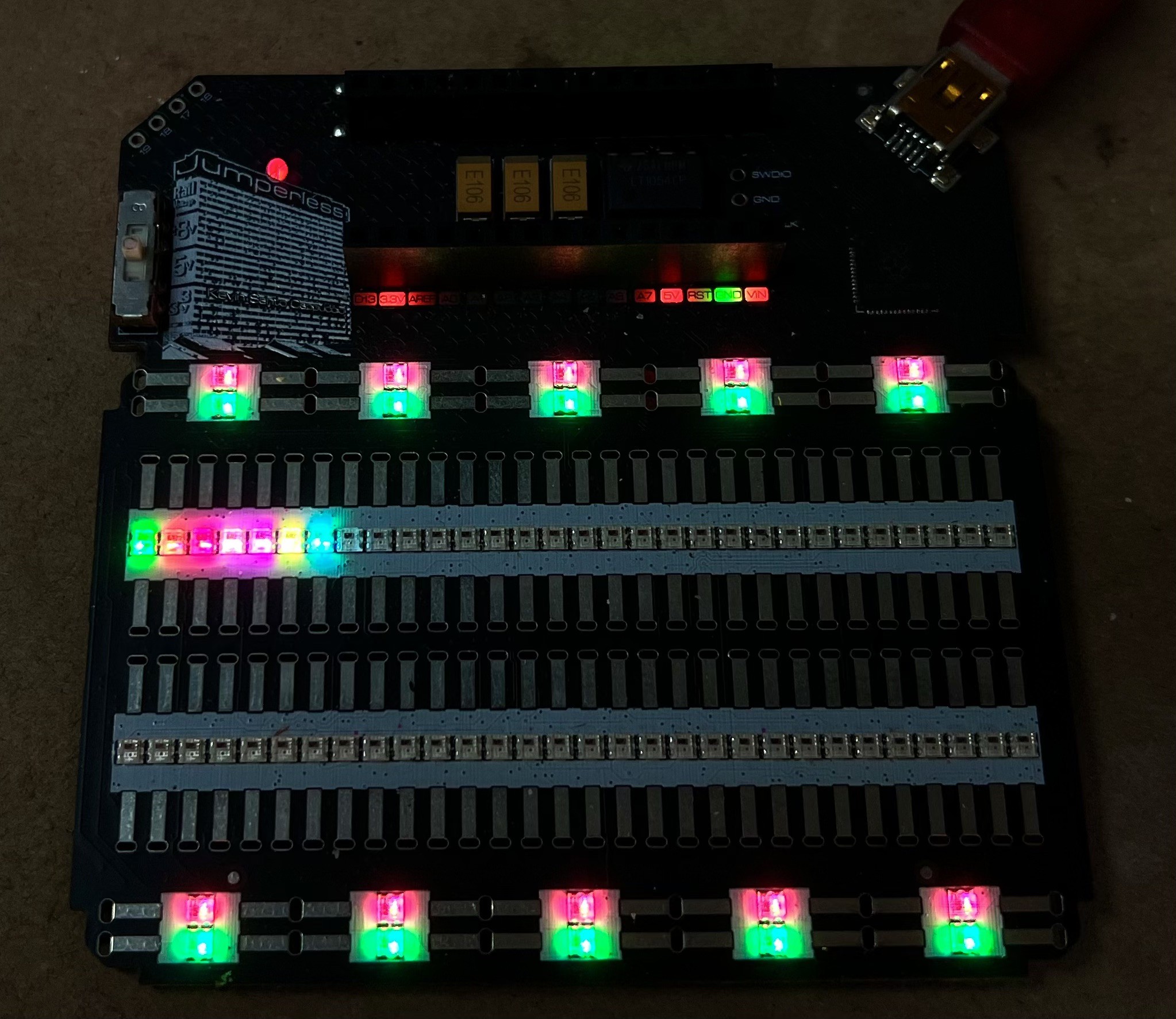

The connections are real and fully analog (-8V to +8V, up to around 1 MHz before signal quality starts to degrade) instead of cheating with some measure-then-simulate setup, although you can do that too if you want to simulate a memristor or to send jumpers over the internet.

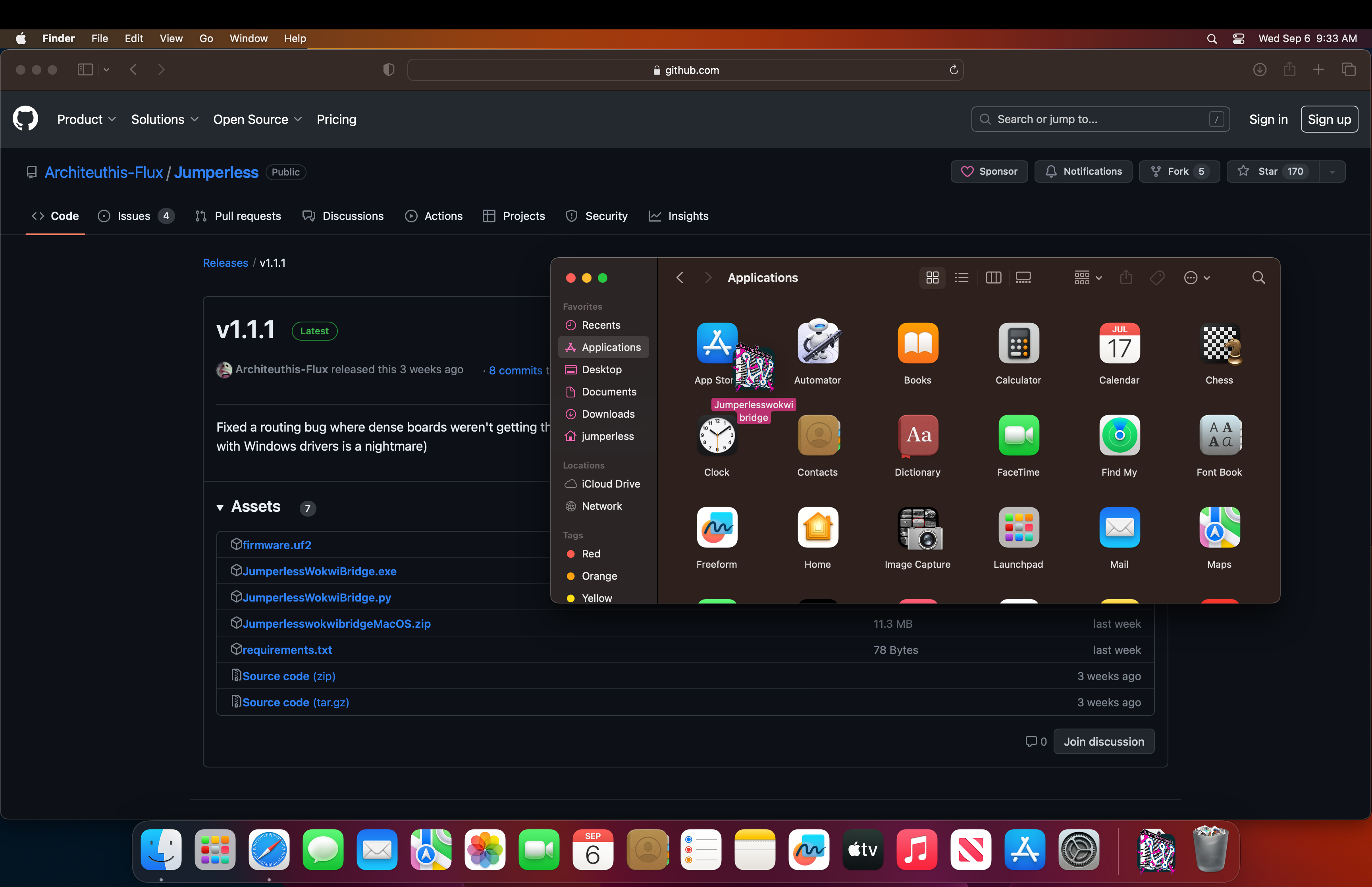

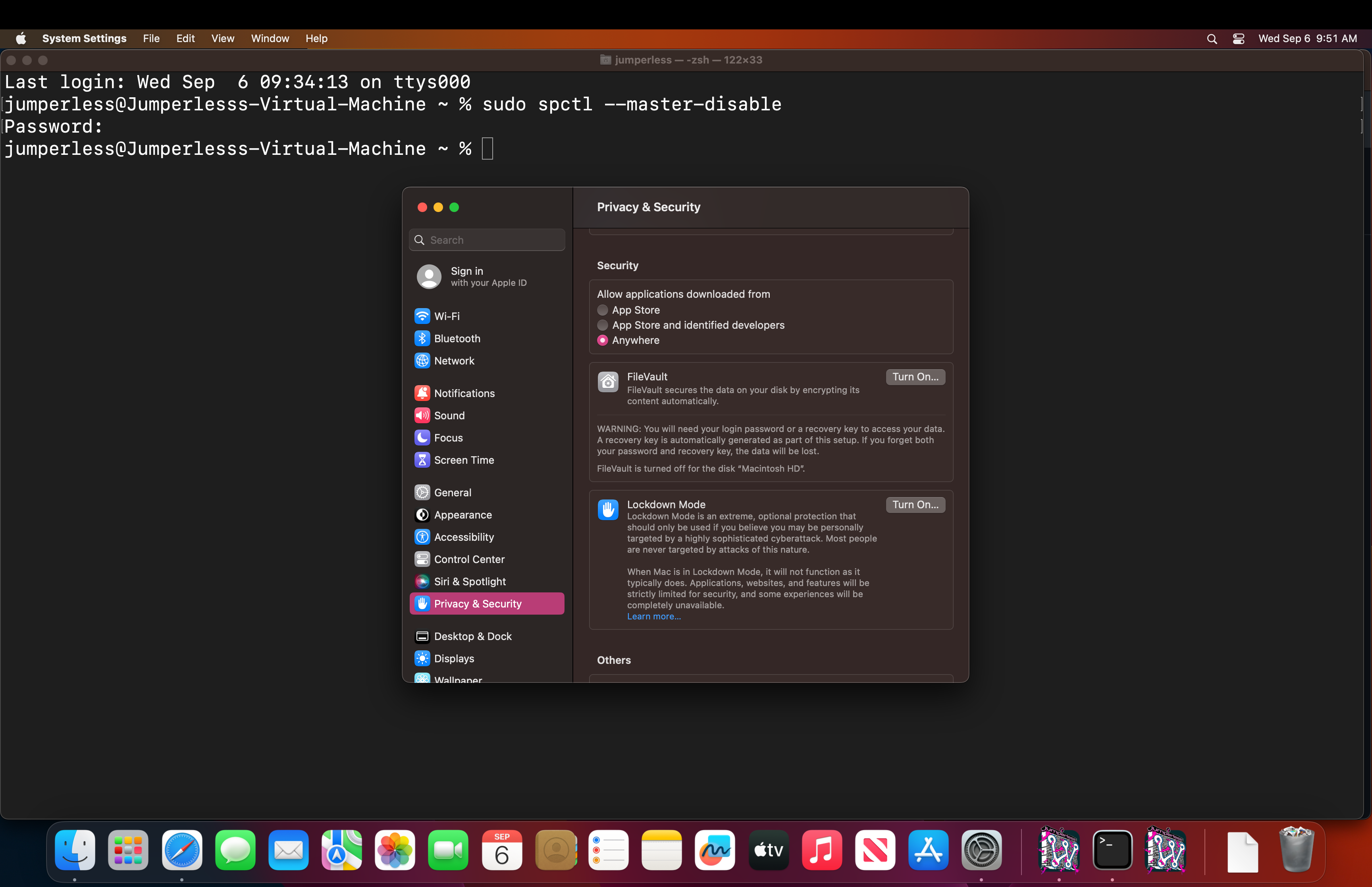

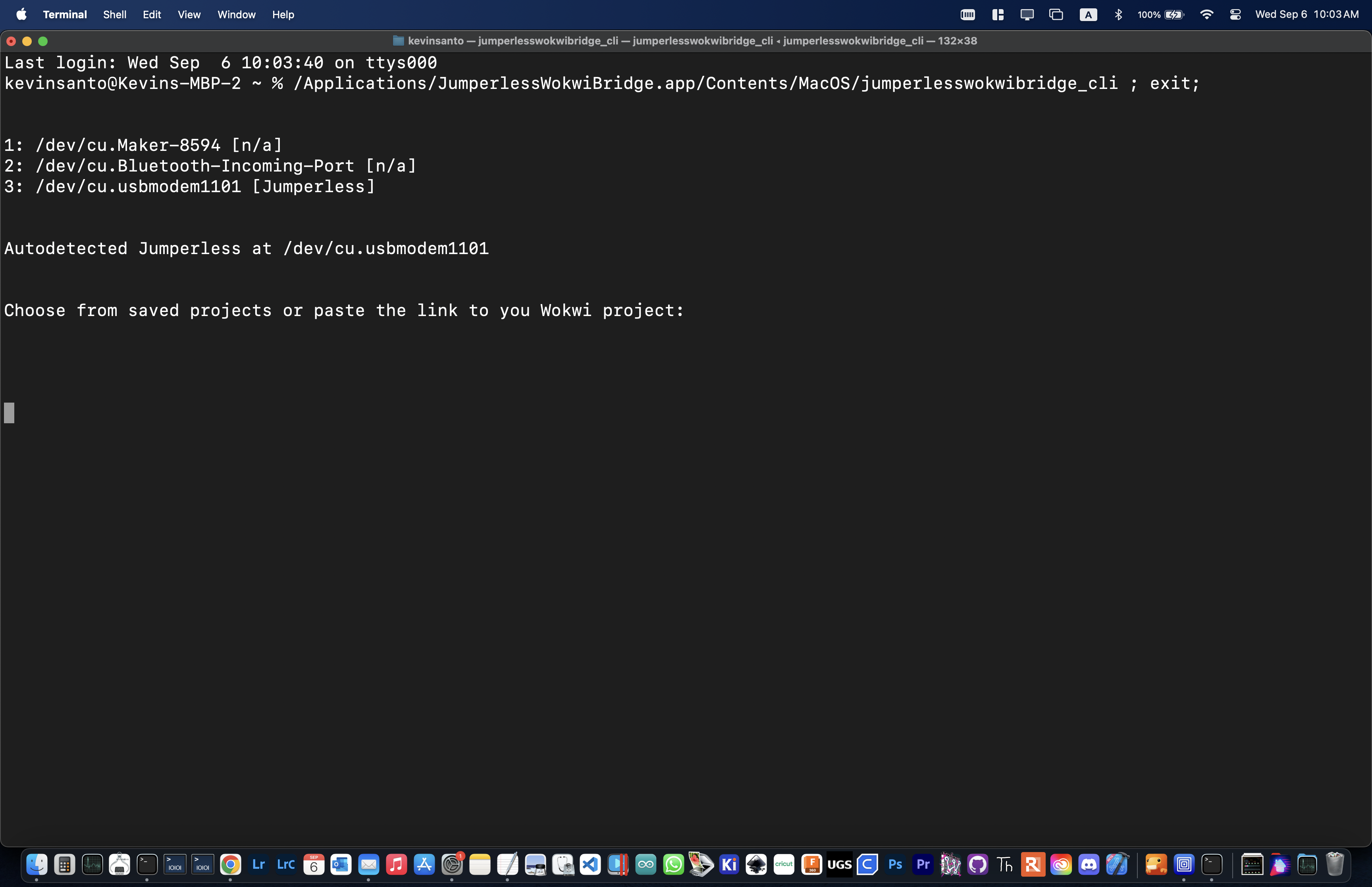

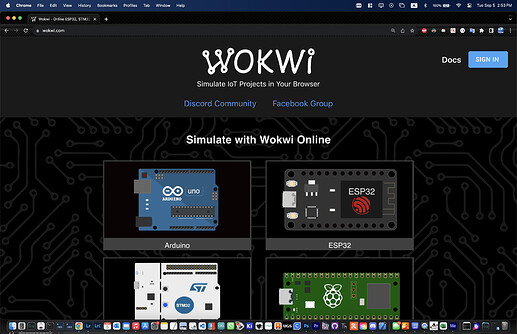

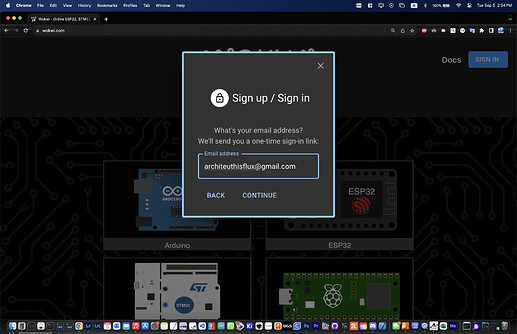

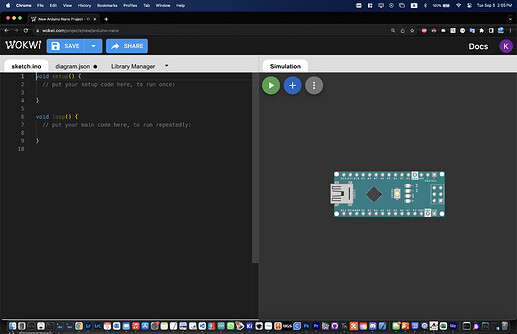

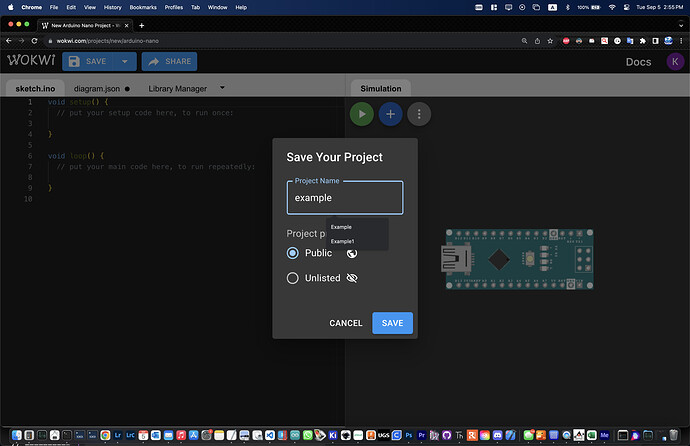

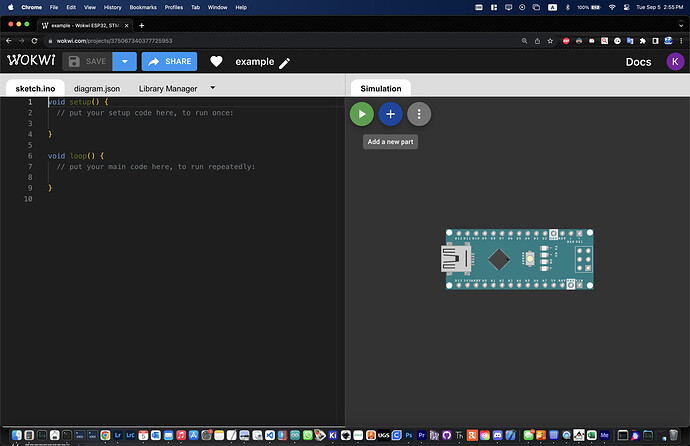

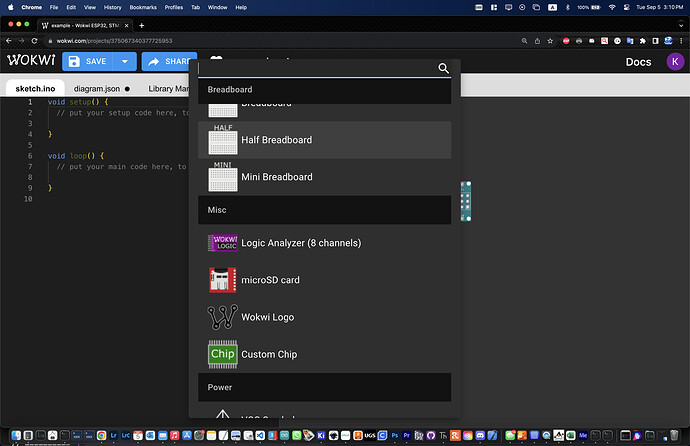

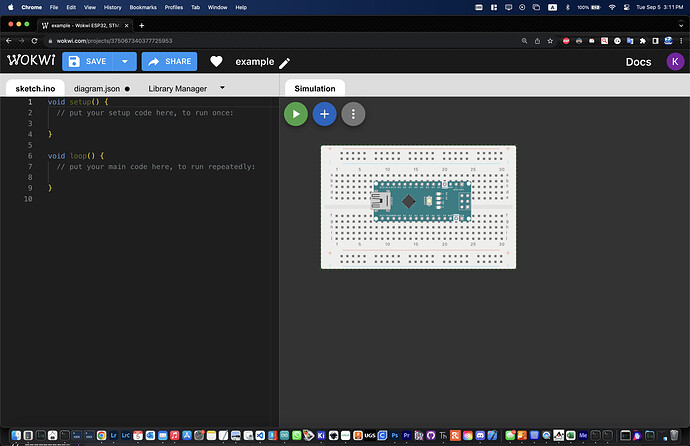

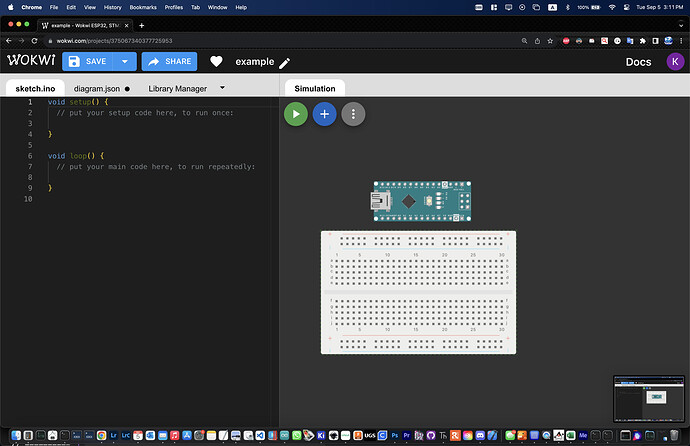

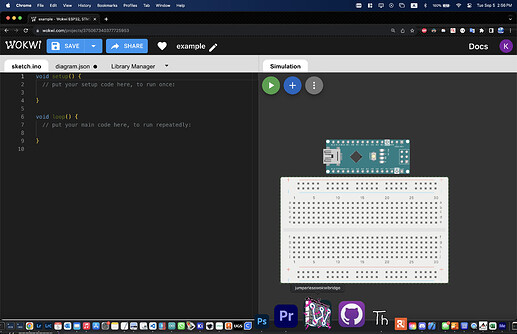

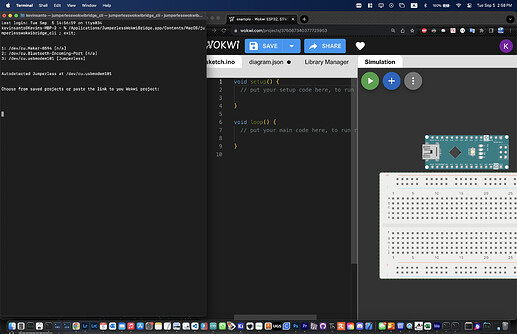

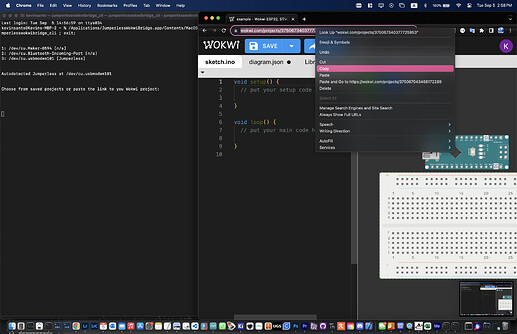

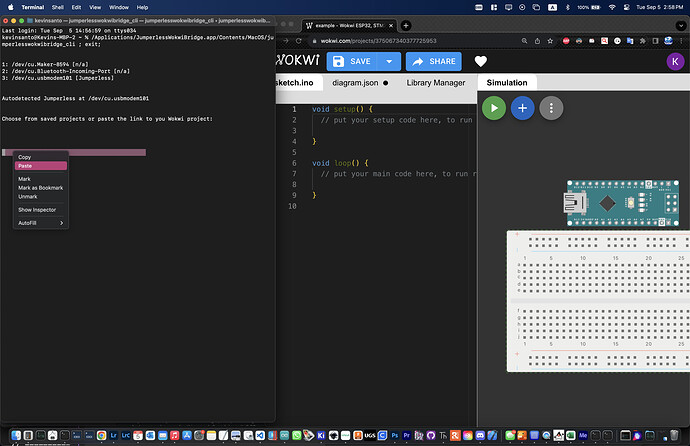

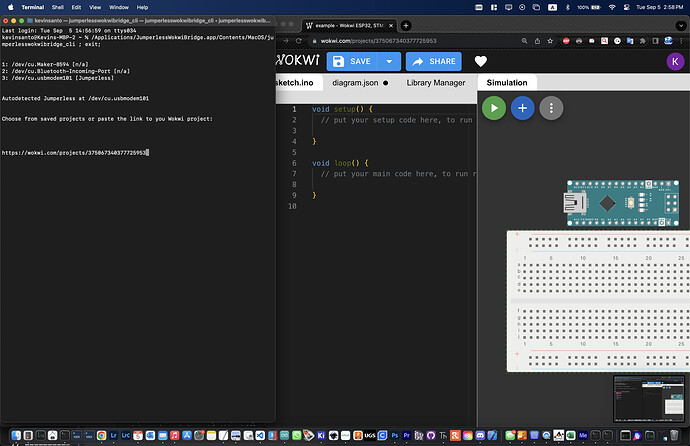

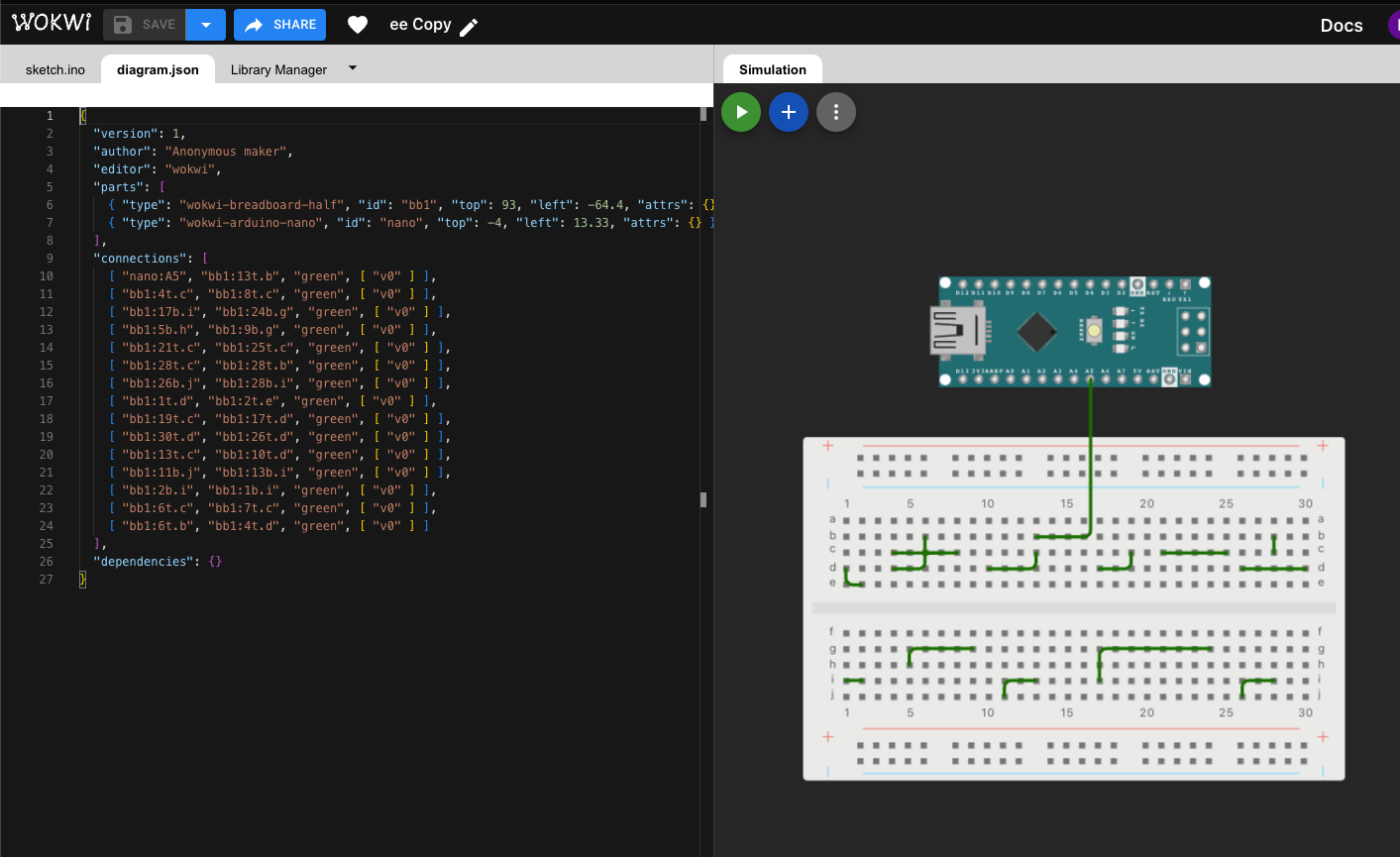

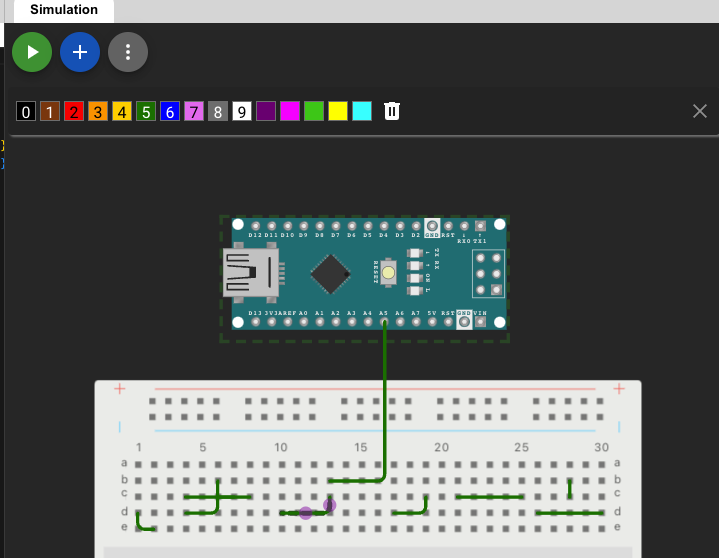

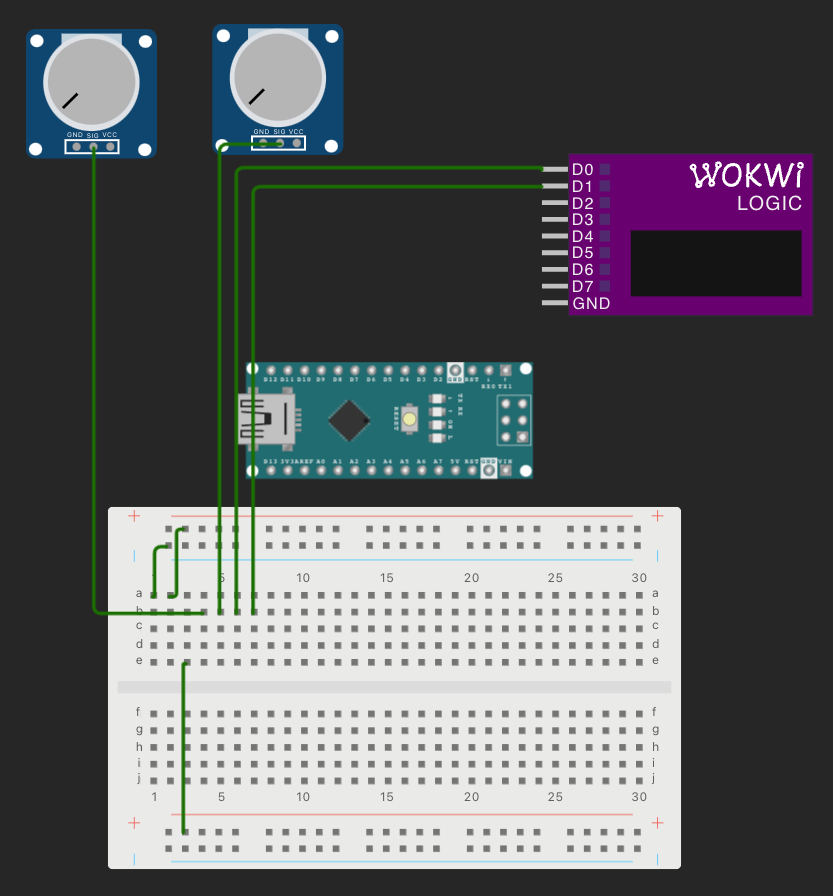

Currently, the best way to make connections is using Wokwi while running the Jumperless Wokwi Bridge app on your computer. It's a Python script and command line interface that automatically pulls any changes you make to your Wokwi project and sends them to the Jumperless.

Here's a video of me connecting an OLED display to an Arduino

It also passes through all the serial communications to and from the Jumperless so you can use the text-based menus to do things like running the wave generators, measuring current/voltage, and looking debug output on the Jumperless directly at the same time.

Pretty soon there will be an Arduino Library where you can make connections and measure stuff with an API that will look something like jumperless.connect(row1, row2); or jumperless.measureVoltage(row); that can either be run on the Arduino Nano (sending commands via UART to the RP2040) or the Jumperless itself.

Hopefully this will allow people to write cool stuff for the Jumperless to do that I haven't even thought of and wouldn't be possible on a regular breadboard.

Also there will be a Python Module that does the same stuff as above, which can either be run in an onboard MicroPython interpreter or on a computer.

Here's another video of me using the Jumperless to figure out the pinout of an LED matrix. I'm actually not faking it in this video, I couldn't find a datasheet.

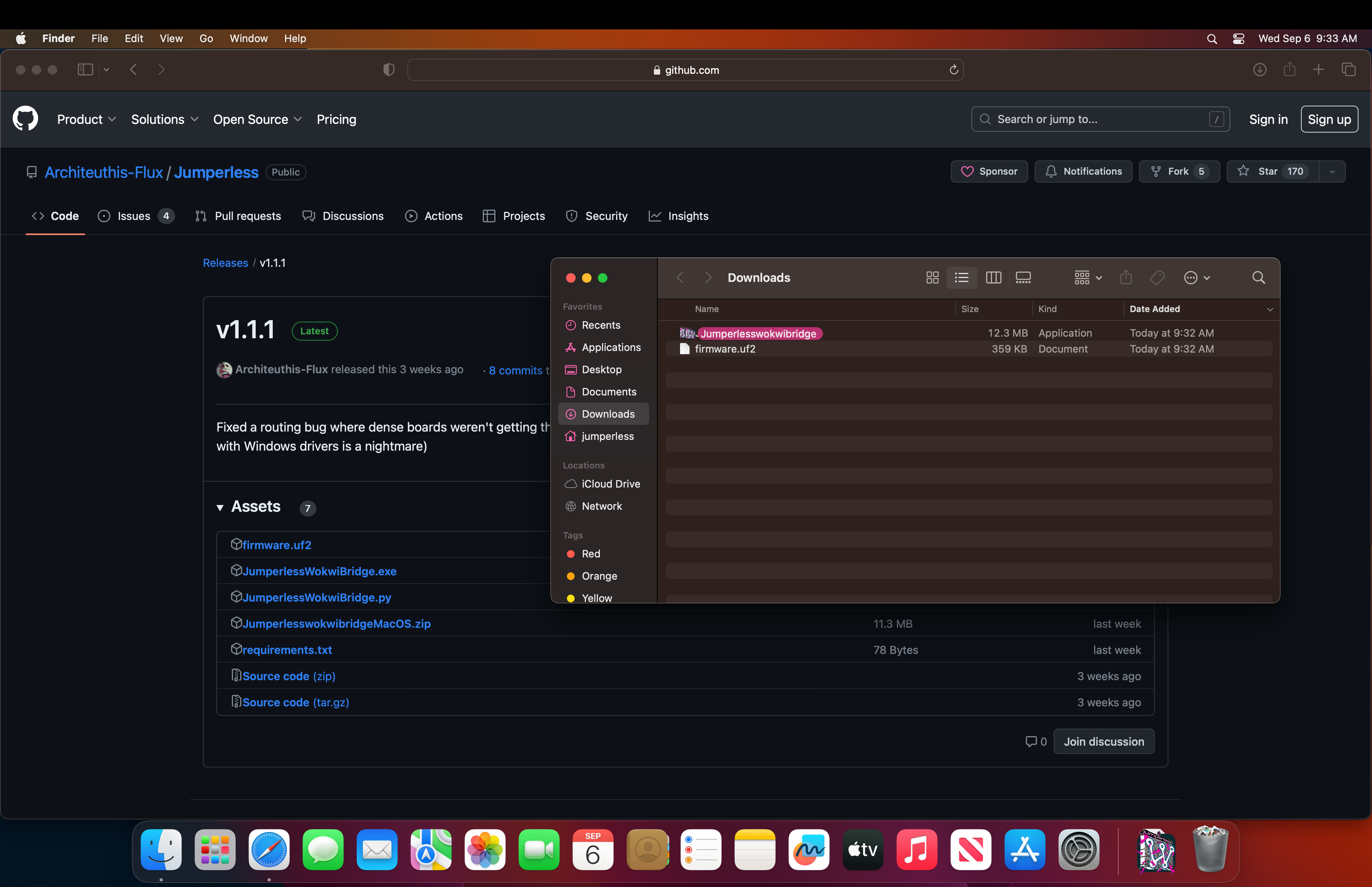

Firmware and stuff

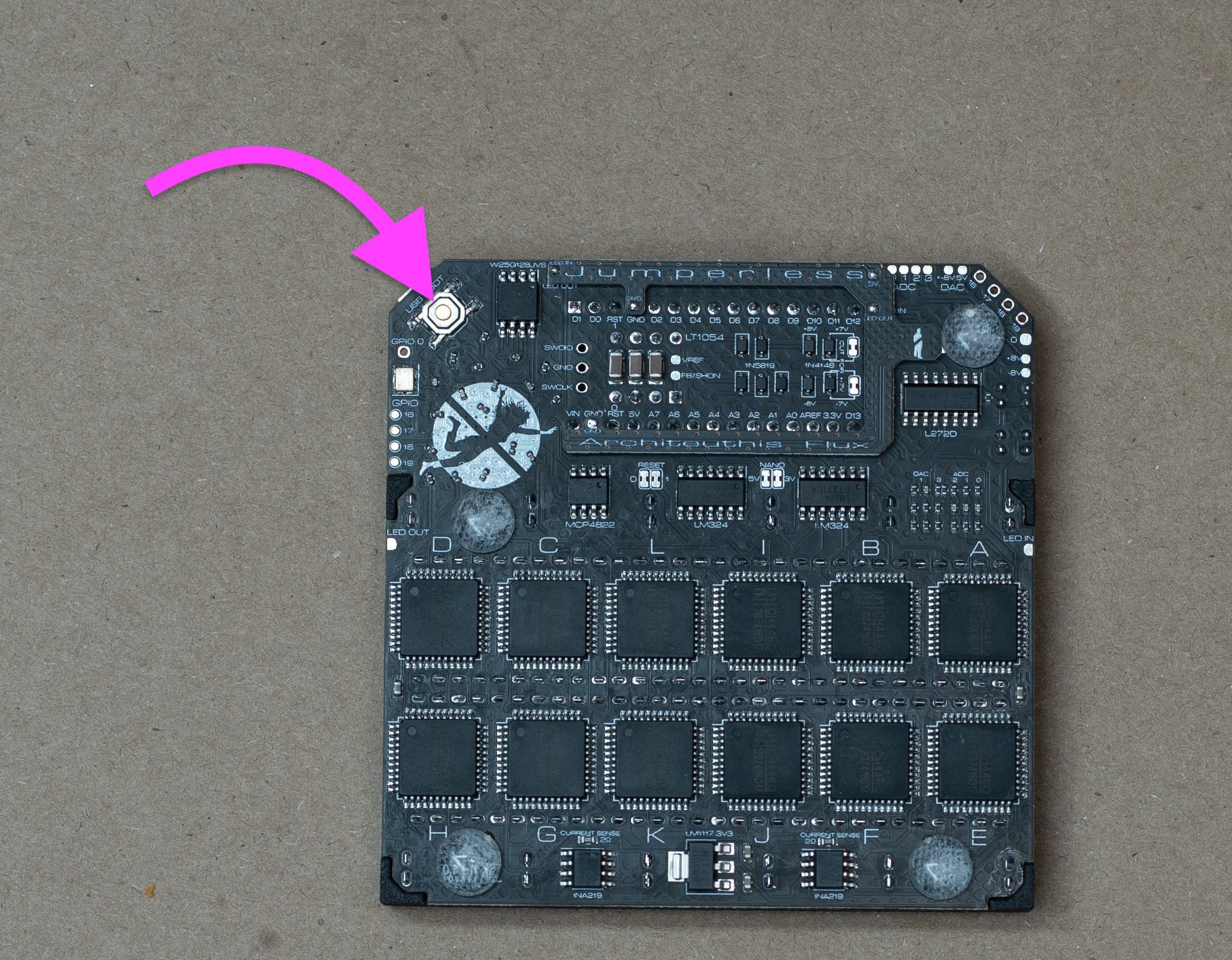

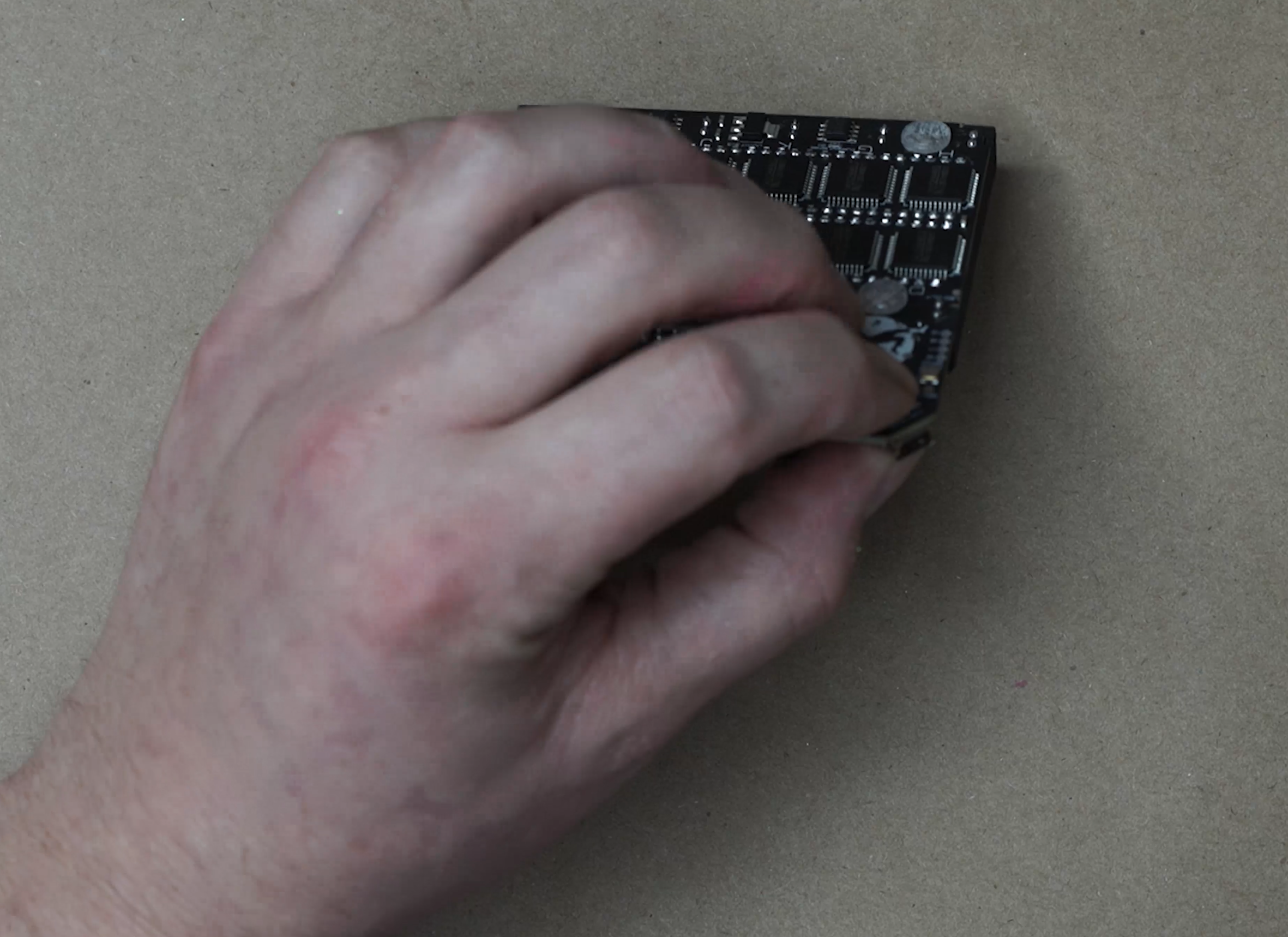

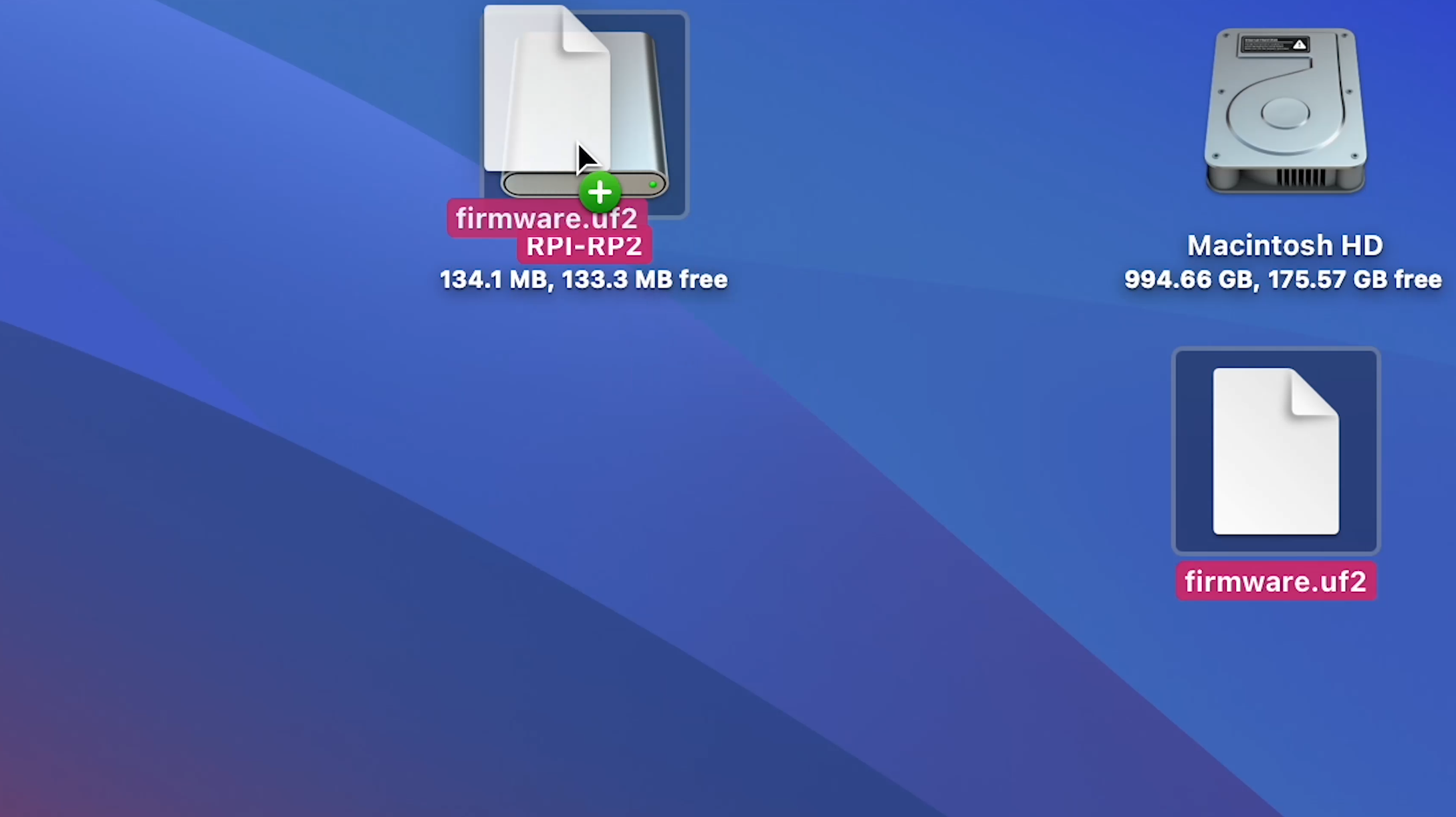

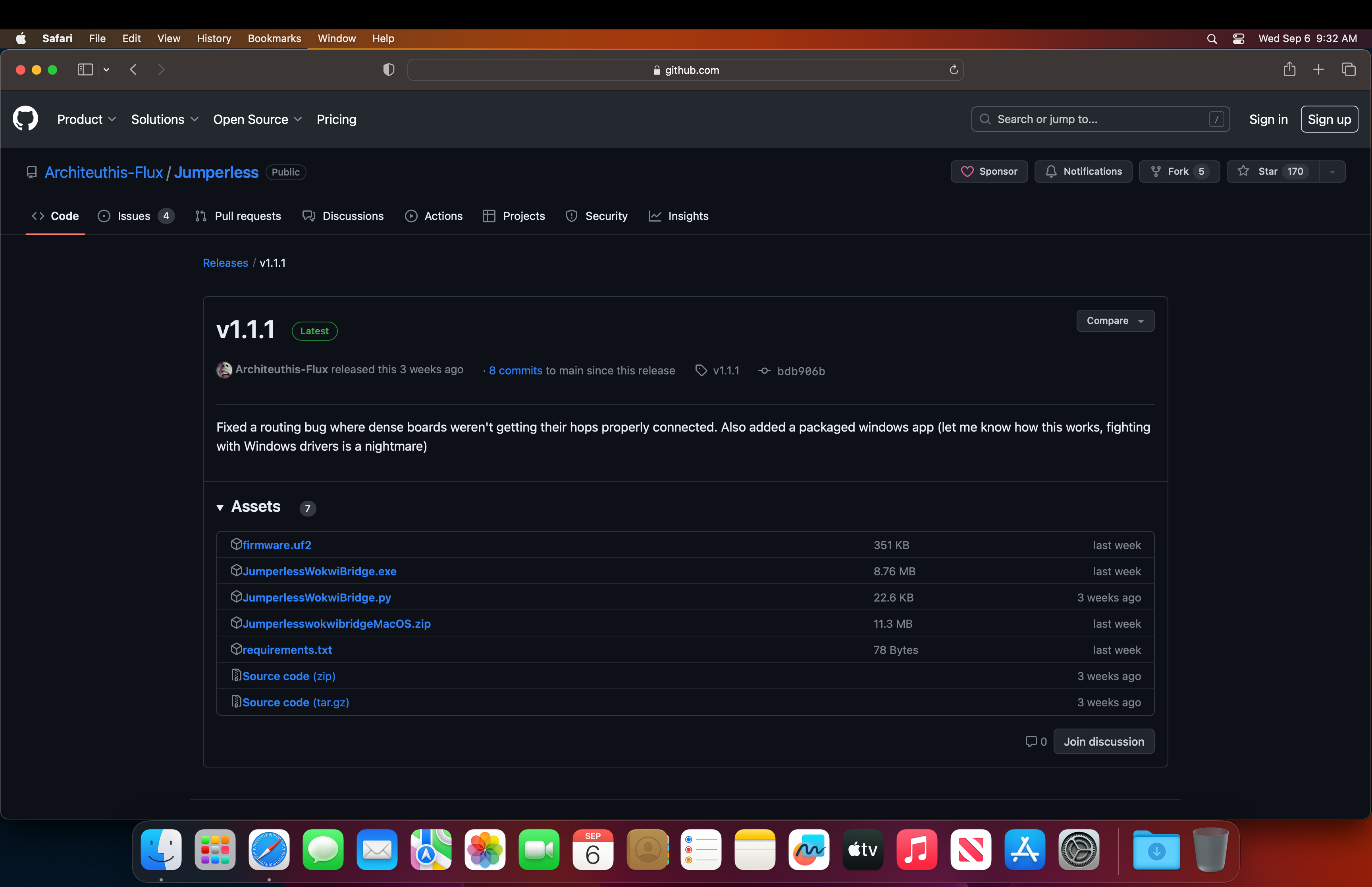

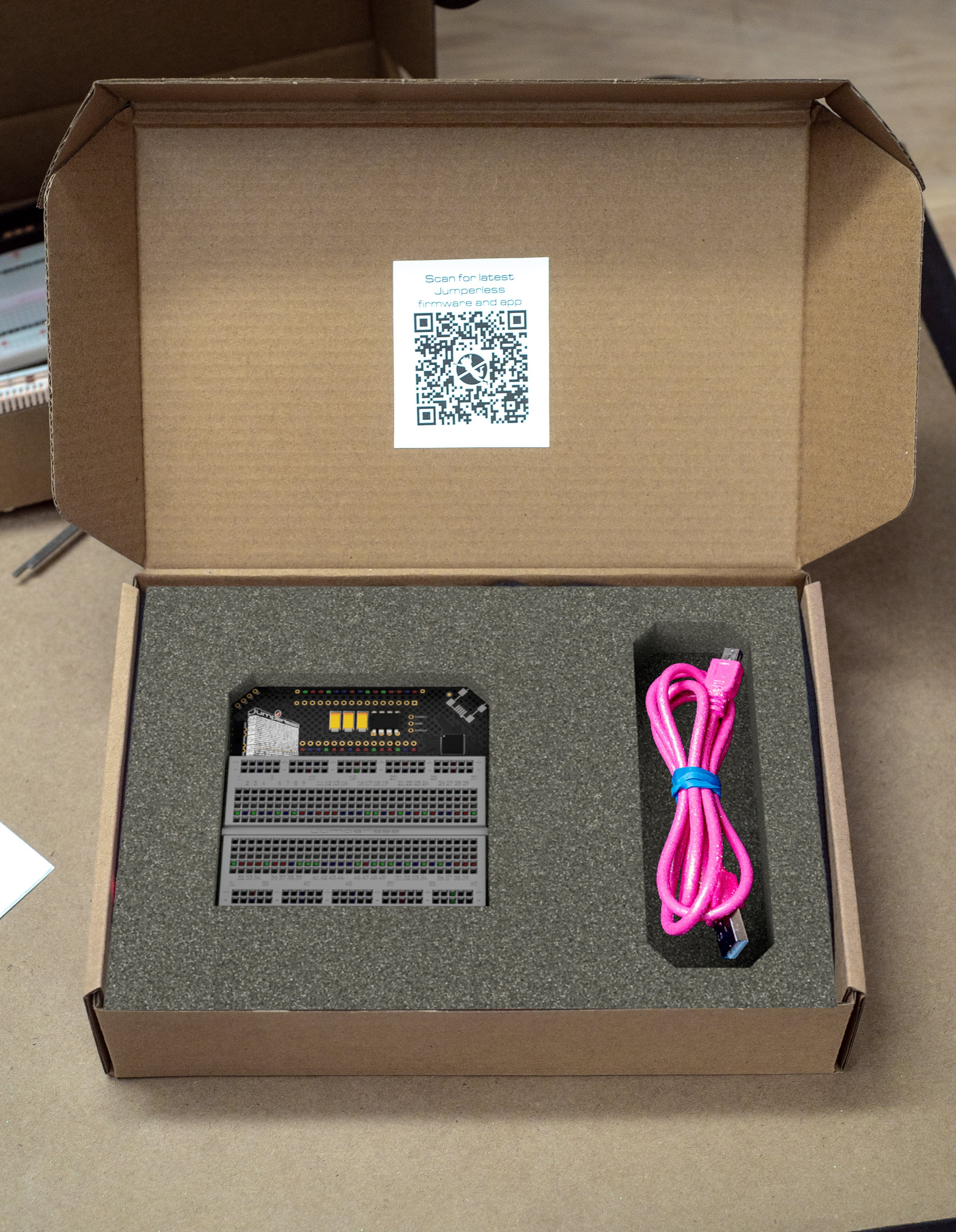

The Jumperless is controlled by an RP2040 and can be programmed exactly like a Raspberry Pi Pico. I spend every waking second of my life working on the firmware so there will be frequent updates. There are prebuilt UF2 files on Github under Releases, so whenever there's an update, just hold the USB BOOT button while plugging it into your computer (with the included pink glittery USB Mini cable,) then drag that UF2 file into the drive that pops up and you're good to go.

The whole thing is open source so you can also edit/fix the firmware however you like (and please submit a pull request on Github to share your fixes)

DACs and Revisions

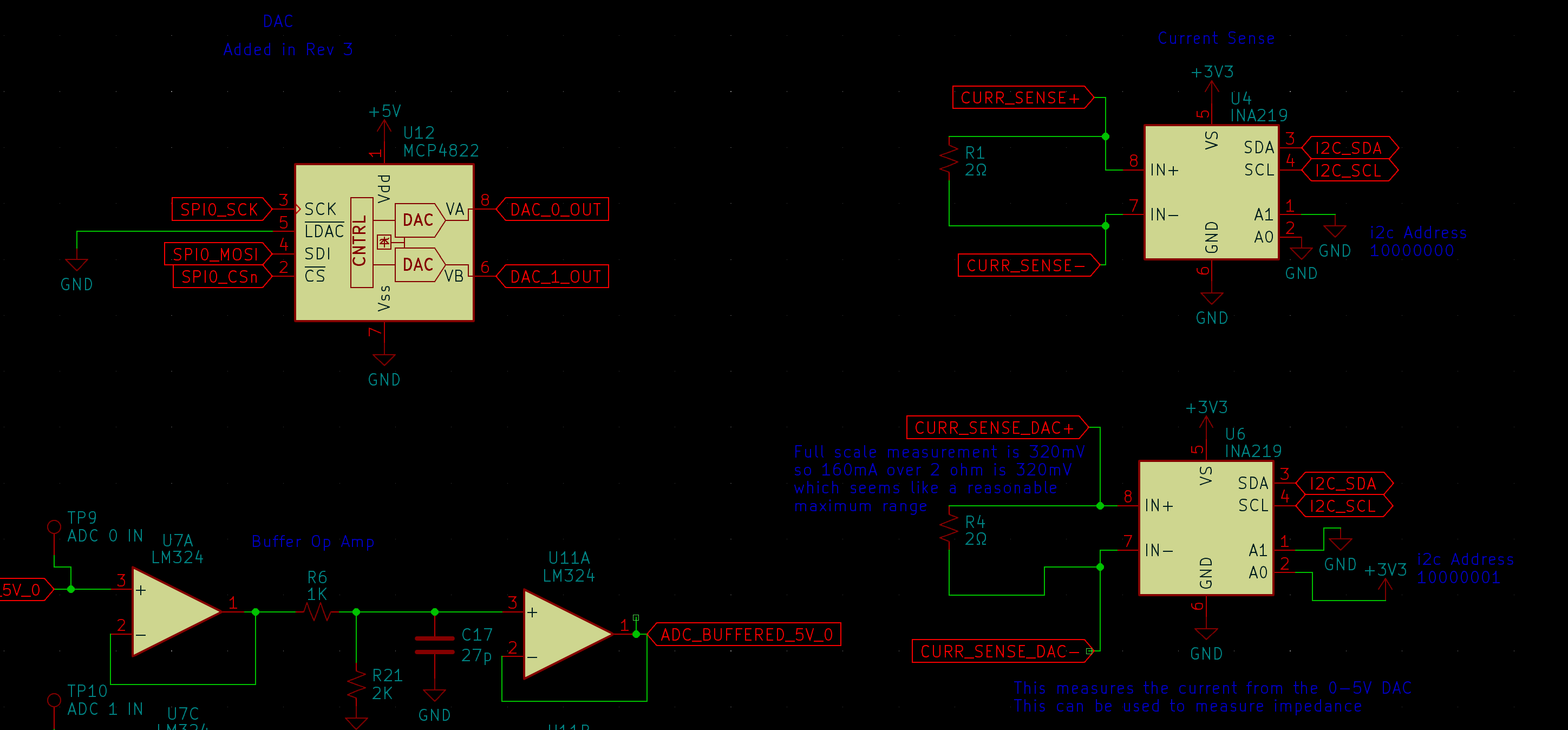

Currently, the ones available are Revision 2, the only major difference between Rev 2 and the soon-to-be-available Rev 3 are the Digital Analog Converters. If you're an audio person that might want to use this thing as a eurorack module or something involving generating audio, I recommend you wait for Rev 3 to be available in a couple weeks. Here's why:

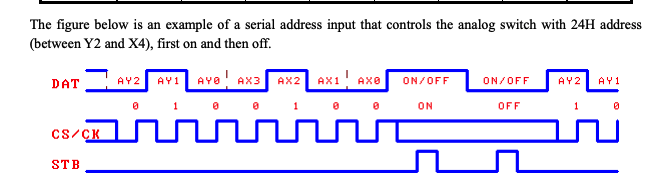

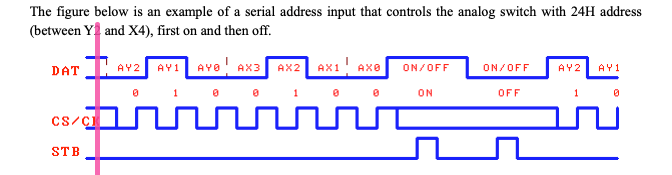

Revision 2 uses 2 MCP4728 12-bit I2C DACs, which work great for setting voltages to be used as an adjustable power supply, but I2C isn't fast enough to send clean waveforms above ~100Hz.

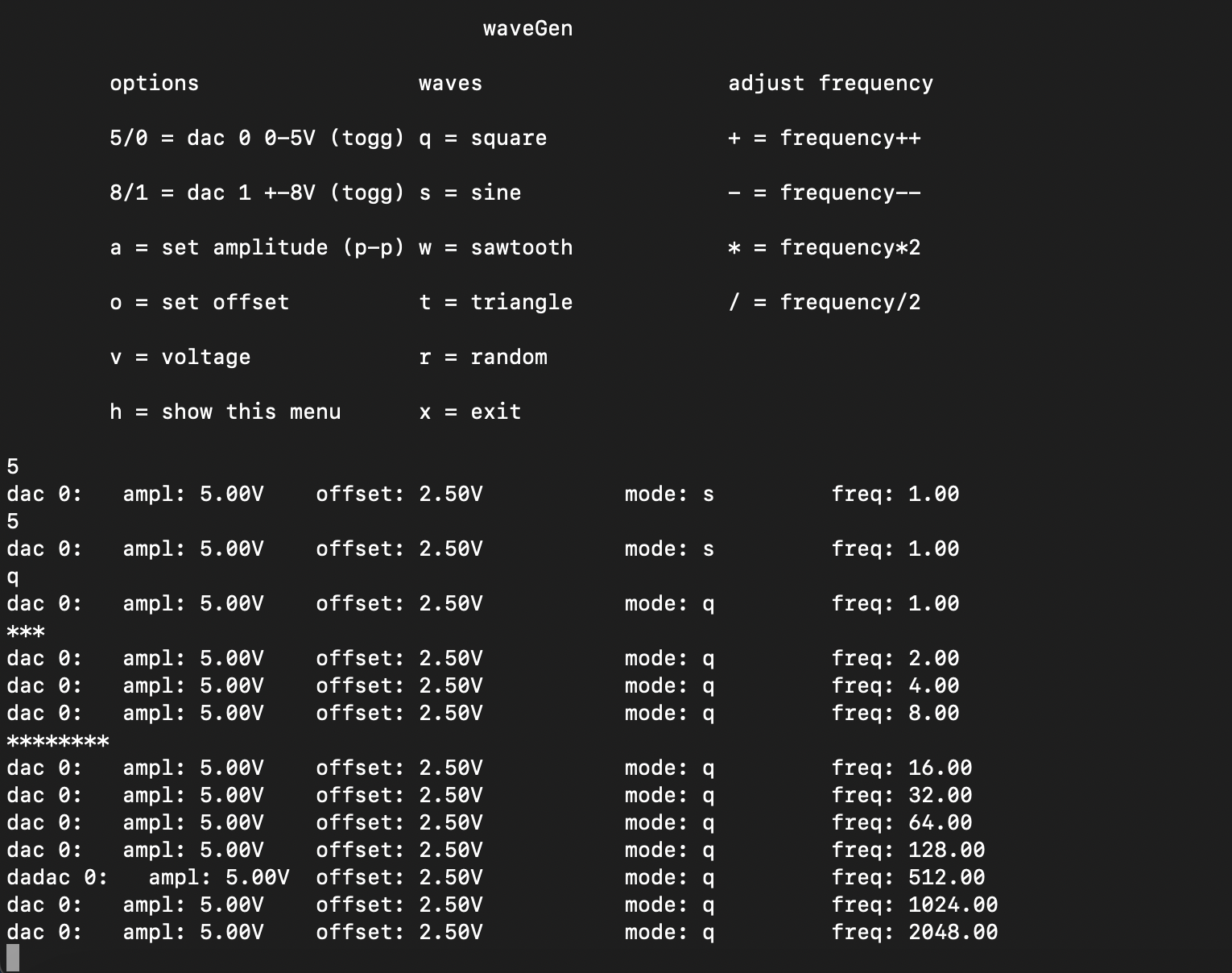

Revision 3 now uses a single MCP4822 2 channel SPI DAC, which is fast enough to make waveforms well above 400KHz. So you could feasibly use the onboard DAC as a Max8 or plugData output, and route the audio output to the breadboard and mess with it in hardware and even send it back in as an input. The software to do that hasn't been written yet but with the upcoming Python Module and Arduino API, it shouldn't be too difficult pull off.

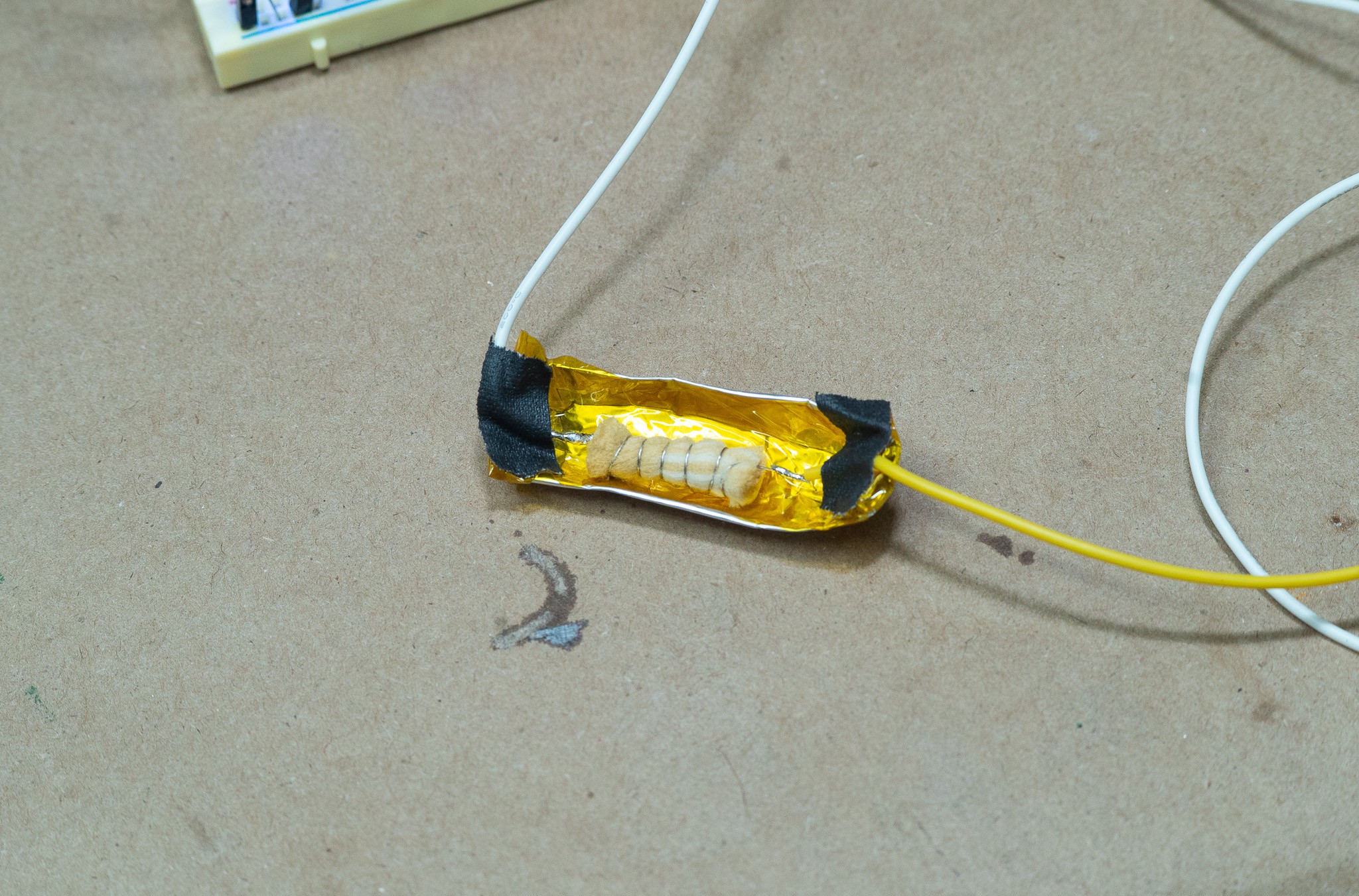

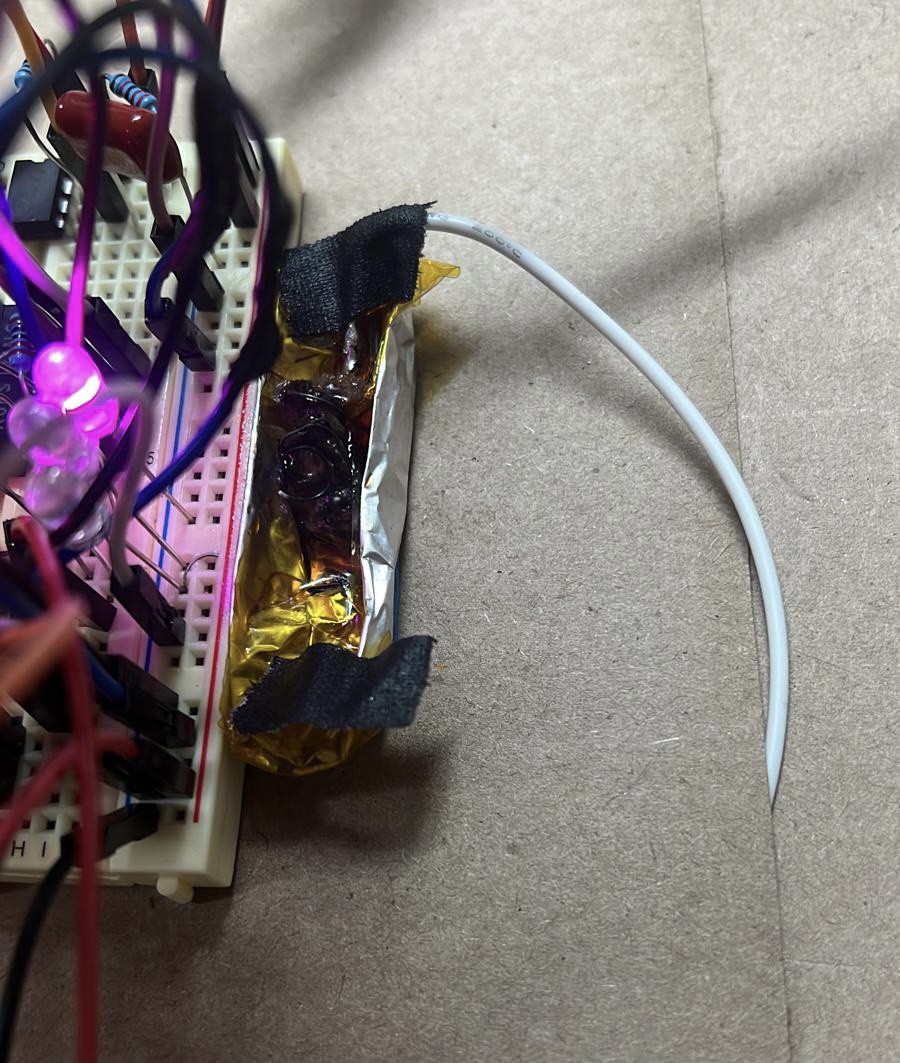

Both of these revisions have their DACs buffered through an LM272D High Power (1A) op amp. Obviously 1 amp would blow this thing up, the power supplies couldn't handle it, and it would go way over the current limit for the crosspoint switches. But the outputs of the buffered analog voltages are broken out to pads in the top corner, so you could drive a smallish speaker directly form that if you wanted to.

The +-8V DAC output is hardwired to one of the 2 INA219 current/voltage sensors so you can always see how much current is being drawn. The other INA219 is...

Read more » Kevin Santo Cappuccio

Kevin Santo Cappuccio

Alexander

Alexander

Kevin Santo Cappuccio

Kevin Santo Cappuccio

davedarko

davedarko

Onchip

Onchip

Such a cool idea :) I'd not heard of those analogue switches before either